Fatherhood by shock: does

marital separation bring about a more equal time allocation among parents?

University of Antwerp - Universiteit

Antwerpen - Centre for Social Policy Herman Deleeck - Authors: Joris Ghysels and Lieve Cornelis - Research papers : 2006

Paper presented at the 28th Annual Conference on Time Use Research (Copenhagen,

16-18 August, 2006); Version 1: July 2006

Abstract

Despite

government campaigning, a changing public perception of the contribution of

fathers to childrearing and rising female employment rates, time use data

continue to show a large gap between mothers' and fathers' childcare time. In

this paper, we investigate if a (largely) exogenous demographic evolution, the

rising rate of divorce, is likely to alter expectations on this issue. More

specifically, we want to know if the fathers' share of active childcare raises

following a separation. This is likely to be the case if they share custody

with their ex-partner.

Yet, it

is also possible that fathers call in other relatives, rely on childcare

services to a large extent or transfer their responsibilities to a new partner

as soon as possible. All the latter would result in a status quo, as far as the

gendered division of childcare time is concerned.

With

data from the 2004-2005 Flemish Families and Care Survey, we show that there

exists indeed a difference in the gender time balance, depending on the family

type of the male partner involved. More specifically, fathers who live in a

reconstituted family with some of their biological children, are significantly

more likely to share care tasks equally with their female partner than other

fathers. Hence, the rise in marital separations may coincide with a more equal

time allocation among parents.

JEL-codes: D13, J12, J13, J16

Themes: divorce, childcare time, gender, time

allocation

1. Introduction

By the

end of the twentieth century, female employment is widely considered to be self-evident.

As a result, more families face the everyday challenge of combining both labour

market duties, household chores and child care. This evolution has given way to

a (somewhat slowly) changing public perception of the contribution of fathers to

household work and childrearing. A ‘modern’ dad is expected to equally share

the burden of all domestic responsibilities which were previously taken up by women

according to traditional gender roles.

Furthermore,

governments have responded to this new social constellation by introducing a set

of measures to facilitate the combination of work and family (European Commission,

2005). Some of these actions (e.g. paternity leave and parental leave targeted at

fathers) try to induce fathers to participate more in child raising.

However,

despite government campaigning, a changing public perception of the contribution

of fathers to childrearing and rising female employment rates, time use data continue

to show a large gap between mothers’ and fathers’ childcare time (Stancanelli, 2003;

Glorieux, Koelet, Moens, 2001; Robinson, 2003; Craig, 2006; Kalenkoski, Ribar, Stratton,

2005). Furthermore, over the past decades the rate of change of the gap was so small

that it makes scholars remark that its closure is virtually out of sight.

Yet, another

societal change of the past decades, the rising divorce rate, may offer prospects

for faster change. In this paper, we investigate whether this (largely) exogenous

demographic evolution is likely to alter expectations. More specifically, we want

to know if the fathers’ share of active childcare raises following a separation.

This is likely to be the case if they share custody with their ex-partner. Still,

it is also possible that fathers call in other relatives, rely on childcare

services to a large extent or transfer their responsibilities to a new partner

as soon as possible. All the latter would result in a status quo, as far as the

gendered division of childcare time is concerned.

Data for

this analysis stem from the 2004-2005 Flemish Families and Care Survey, a survey

with representative data on families with children below 16 in the Flemish region

of Belgium. Before tackling the data, however, we go over results from previous

research (section 2) and present some basic data about fathers’ experiences with

divorce in Flanders (section 3). In section 4 we discuss the dataset in detail

and elaborate the empirical analysis. We show the differences in care time

according to a typology of fathers and confront this typology with other explanatory

factors in a multivariate analysis. Section 5 concludes.

2. Previous research about parental care time

In the following

paragraphs, we synthesize the most important findings of the relatively scarce literature

on childcare time. Anxo, Flood and Kocoglu (2002) compare the time allocation

of parents in France and Sweden. Their ‘double hurdle’ analyses of time diary

data indicate that parents tend to spend less time on childcare when their

children grow older, that lowly skilled parents tend to spend less time on childcare

and that women tend to be more sensitive to all kinds of explanatory factors. Their

analysis suggests, moreover, that institutions matter. Swedish fathers spend more

time with their children than the French, but the French tend to compensate for

the working time of the mothers while the Swedish do not. According to the

authors this may be attributed to the Swedish combination of a wide offer of childcare

services and extensive career flexibility regulations, which reinforces women’s

relative power in marriage and allows for a considerable externalisation of the

care burden.

Hallberg

and Klevmarken (2003) focus on the childcare time of Swedish dual-earner couples.

Their analysis of time diary data confirms the effect of the age of children. Furthermore,

it shows that Swedish parents treat their partner’s childcare time as a complement

to their own time rather than as a substitute.

Neuwirth

(2004) analyses primary childcare activities from the 1992 Austrian time use survey.

He finds that parents’ childcare time is mutually positively correlated, while

being inversely related to the own job time. Moreover, Austrian women tend to compensate

for their partner spending much time on his job, while men do not. This gender

differential and the overall observation of the smaller responsiveness of men

to observed variation in their household situation suggests that the male chauvinist

model is still important in Austria. Furthermore, Neuwirth’s ‘two stage least

squares’ analyses show clear links between the various time allocation decisions,

which indicates Austrian parents’ need to accommodate privately for, say, an increase

of their job time.

Deding and

Lausten (2004) analyse time diary data of Danish couples, which they enriched with

official register data. They compare market work with non-market work and differentiate

between housework and childcare within the latter category. The results

indicate that there exists a trade-off between market work and non-market work,

but that childcare is relatively ‘untouchable’. If the time for non-market work

is squeezed it is other categories of activities that shrink, not childcare. Moreover,

the authors confirm the previously found positive association between male and female

childcare time.

Kalenkoski,

Ribar and Stratton (2005) differentiate between market work, primary childcare

time and secondary childcare time and analyse British time diary data. As in

the French and Swedish case, highly skilled parents tend to spend more time

with their children and childcare time levels off as the children grow older. Interestingly,

primary childcare time is concentrated among the youngest and secondary

childcare time tends to rise somewhat with the age of the children before both categories

disappear altogether. They also examine parents’ child care time among three

family types: married, cohabiting and single-parent families. They find no differences

between married and cohabiting partners with regard to time devoted to

childcare and to market work, but single parents appear to spend more time on

child care and less time on market work than other parents.

Paley (2005)

considers the timing of parental childcare and includes both ‘active’ childcare

time and ‘passive’ childcare time, conditional on the other parent not being actively

caring at the same moment. She uses data from the 1997 time diary supplement of

the US Panel Study on Income Dynamics. Paley observes how the job schedules of parents

can effectively ‘force’ men to enhance their childcare time relative to other fathers.

However, she also finds that mothers do not treat their partner’s increase as a

substitute, but rather exhibit compensatory behaviour. In other words, when arriving

home later than the father and the children, the mother will spend relatively more

time with her children than other mothers. Among men, though, there is no such

compensatory behaviour.

Ghysels

(2004, 2005) analyses a 1997 ECHP-dataset of two-partner households in a simultaneous

equations framework incorporating both childcare time and job time. His

analyses show that childcare time is positively correlated among Danish,

Belgian and Spanish parents. However, the simultaneous equations framework revealed

no direct impact of a respondent’s job time on the own childcare time, nor his or

her partner’s, except in Belgium. In Denmark and Spain the link between

childcare and employment proved restricted to a one-way relationship with the

amount of personal childcare determining one’s job choice.

Besides

studies about parental childcare time in general, some researchers investigate childcare

time spent by one of the parents. Kimmel and Connelly (2006) focus on time mothers

spend with children because women tend to experience conflicts between market

work and family responsibilities more intensely than men do. They estimate a simultaneous

four-equation system using data from the 2003 American Time Use Survey. The

results of their analysis show that mothers’ time with children does not

respond to price or demographic changes as pure home production or leisure do.

As a result, maternal childcare time should be considered a distinct time

spending category, next to paid labour, leisure and pure household work production.

Furthermore, Kimmel and Connelly (2006) notice important differences between

time allocation on weekdays and during weekends. Therefore, a separate analysis

of timebetween these types of days seems appropriate.

Stancanelli

(2003) elaborates several regression analyses on ECHP-data [1] to investigate

fathers’ care time. Her results show that time allocated by fathers to child care

is responsive to their own hours of paid market work [2] (-) and to their

spouses’ paid working hours (+). In addition, caring time by fathers is found

to be positively related with employment in the public sector and with a high

level of education of the spouse. Self-employed men appear to spend substantially

less time caring for their children.

Apart from

childcare time, several researchers examine time people spend on domestic work

such as washing, cleaning, cooking meals, keeping the house in good order, etc.

One of the main conclusions from this strand of the literature is that women still

dedicate considerably more time to household chores than men, although the division

of household work has become slightly more gender equal over the past decades –

principally due to the fact that women do less now than they did before (Craig,

2006; Baxter, 2002; Stancanelli, 2003; Robinson, 2003).

A main

societal evolution of the twentieth century, the increased divorce rate, might alter

expectations on the balancing issue. During the various stages between a first and

second marriage, men are likely to acquire some experience running a household on

their own. This experience, as little as it can be, can be expected to lead

divorced men to carry out more household duties in their second marriage (or cohabitation)

than in their first marriage. This theoretical expectation is not immediately corroborated

in the literature. Most studies find that remarried woman continue to do the

bulk of housework (Demo & Acock, 1993; Pyke & Coltrane, 1996). Yet,

Ishii-Kuntz and Coltrane (1992) observe that remarried husbands in the US bear slightly

more household chores than husbands in their first marriage (National Survey of

Families and Households (NSFH) 1987-88). This result suggests that the time men

dedicate to household tasks has changed due to their experience of a divorce. In

our data, we will investigate whether this finding holds for childcare time as

well.

3. Fathers and divorce in Flanders

Recently,

Belgium has become one of the European countries with the highest rate of divorce.

[3] Statistics for Belgium show that two out of three couples who split up,

have children. Furthermore, many of these children are found to be very young.

Of all the children whose parents divorced in 2003 (about 40 000), nearly half

was 12 years old or younger at the time of divorce.

From a

social perspective, it is very interesting to examine what transformations with

regard to family structure take place after a divorce. Lodewijckx (2005)

investigated the living situation of all children in Flanders and found that

25% of Flemish children do not live with their biological parents. About 7% of Flemish

children stay with one biological parent and his or her new partner. The vast

majority of them live with their mother and a stepfather. When children stay

with only one parent, it almost always concerns their mother (11% of all children

have a single mother versus 1,6% who have single fathers). Moreover, the evolution

of children’s living conditions differs depending on whether they stay with their

mother or their father. One out of five divorced men [4] are part of a new family

within four years after their divorce, as opposed to just one out of ten women

(Corijn, 2005b). Therefore, children of single mothers are proportionally more likely

to stay in a single-parent family for a long while.

Corijn (2005a

and 2005b) investigated the marital situation of Flemish men and women four

years after their divorce. She observed that after this time interval 12% of young

men are single fathers. Other men have found a new partner and live together

with children, who can either be their own children from a previous marriage, the

children of their new partner or new children they join with their new partner.

Yet, in practice

the children involved are generally not the father’s own children, because

children of divorced couples usually stay with their mother. In Flanders, the mother

is very often (nearly automatically) given custody over the children, even though

the Belgian government has recently taken action to install residential co-parenting

arrangements as the norm. Given the current practice, most divorced fathers have

little opportunity to spend time with their own children. Moreover, there is no

systematic registration of co-parenting arrangements, which renders it a

difficult topic for empirical research.

4. An empirical analysis of paternal care time

The description

of the current divorce situation in Flanders - as provided in the previous

section - warrants a more precise definition of our research question. Most divorced

men in Flanders do not experience a transitional period of single parenthood. At

most they experience a type of partial single parenthood if they join custody

with their ex-partner. For most fathers this is not even the case and their

contacts with their children remain limited to (weekend) visits. Moreover, most

divorced fathers quickly form a new family and, hence, have every opportunity to

return to previous habits of unequal sharing of care time. Nevertheless, even

without the actual experience of the full sole responsibility for a household

with children, the divorce experience may lead to an increased involvement in

care time and household chores. Divorced fathers may have come to value the relationship

with their children more than they did before. Alternatively, they may also have

come to recognise the importance of an equal sharing of household responsibilities

for a lastingly successful relationship. Consequently, we will investigate

whether fathers living together with a partner show a different involvement in care

time, depending on the type of family they live in. For this analysis, we will

use a new Flemish dataset, which we describe below.

4.1 Data from the FFCS

The

Flemish Families and Care Survey (FFCS) was elaborated to provide data for a micro-distribution

analysis and contains information on income sources, expenses, care needs, time

use and the use of care services of families with children. It is coordinated

by the Centre for Social Policy Herman Deleeck (University of Antwerp) in

cooperation with the Flemish governmental organization Kind en Gezin [5] (Child

and Family) and the Flemish Fund for the Social Integration of Disabled Persons

(VLAFO) [6].

The

research population consists of families with a least one child between 0 and

15 years old who reside in the Flemish region [7]. The sample is divided into

four subsamples, representing four types of families. The largest group consists

of young families with a least one child under three years. A second group is

formed by ‘older’ families having at least one child between 3 and 15 years

old. Apart from these two groups, who were randomly selected from the National

Population Register, the sample is completed with two smaller subsamples, consisting

of poor families and families having a disabled child. The subsamples were randomly

selected from the client databases of Kind en Gezin and VLAFO respectively. For

this paper, only the samples from the National Population Register are used.

The time

use part of the FFCS refers to activities schedules to be filled by every parent

in the household for two days (one weekday and one day of the weekend, activities

on a quarterly basis), an employment matrix spanning a full week for every parent

and a care schedule for every child of the household (for a full week, on the basis

of a half hour). For the purpose of this paper, we could rely on 920 father’s activities

schedules of a weekday and 937 father’s activities schedules of a Saturday or Sunday.

These data were weighted to produce results representative of the full population

of families with at least one child younger than sixteen years old.

4.2 Fathers and care time in the FFCS

As

stated in the introduction to this section, we want to distinguish fathers on

the basis of their marital history. In our dataset there is no retrospective

data on marital history. However, detailed information is collected on the relationship

between the various family members. Consequently, we can differentiate between

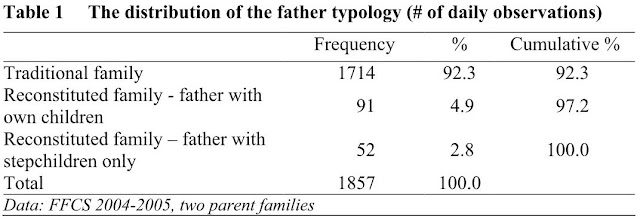

three types of fathers.

The

first type groups those fathers living with children who are biologically

linked to both themselves and their spouses. These form the large majority of

the Flemish population and account for 92% of our sample. The second largest

group is constituted by fathers who live in a reconstituted family, but have a

biological link with at least one child in the household (5% of the sample).

Note that this can relate to the rare occasion of a father enjoying the custody

of his child(ren) from a former relationship, but is more likely to have to do

with offspring of the new relationship.

Moreover,

it should be noted that we cannot distinguish between men who became father for

the first time in the current relationship and fathers whose children from the previous

relationship live with their ex-partner. Consequently, the relationship data allow

no perfect delineation of the marital history of the fathers, but rather

provide a cross-sectional view of the biological and other links between the

parents and the children they take care of. Our final type of fathers refers to

those who live in a reconstituted family without any children who are

biologically linked to themselves (3%). Recall from section 3 that Flemish

fathers tend to enter this type of situation quite quickly after their divorce.

[8] Some, but not all, of them become fathers of the second type after a while

Before

describing the dependent variable, it should finally be noted that our dataset

is restricted to fathers living with a partner. There were only an insufficient

number of observations of single fathers, not surprising given their minority

position in Flemish society.

The

dependent variable of our analysis is primary care time. Parents were invited

to indicate any of six care activities (childcare, medical care, watching over

the children, play and related activities, transport for the child, other care for

own children) and other activities they combined with these care activities. Care

time is counted as primary care if in a given quarter only care activities are

reported or if care time is the only active act presented in the quarter (e.g.

playing with the children and resting are jointly noted). In the case of active

care activities marked jointly with active non-care activities, the care

activities are counted proportional to the total number of activities mentioned

(mostly one out of two, thus 0.5).

While

primary care time is in the focus of our attention, it is not just the number

of hours spent that is of interest for our analysis. More precisely we want to

know the balance between the mother and the father as far as care time is

concerned. Therefore, we will investigate two dependent variables: the amount

of time spent by the father and the proportion of this time in the total

parental care time (mother plus father).

Following

the suggestion of Kimmel and Connelly (2006) and given the predominance of full

time jobs among Flemish fathers, we additionally split our analysis between weekdays

and days of the weekend. In Table 2 and Table 3, the average number of quarters

of an hour fathers spend on primary care and fathers’ time as a proportion of

total parental care time on weekdays and weekends are presented. First, we

observe in the tables considerable differences between weekdays and days of the

weekend. An average Flemish father spends 1h 56’ on primary care for his children

on a typical weekday, while his care time rises to 3h 23’ on a Saturday or Sunday.

Furthermore,

ANOVA-analyses indicate significant differences for both dependent variables

between traditional fathers, fathers living in a reconstituted family with own children

and fathers living in reconstituted families with stepchildren only.

On weekdays

(see Table 2), fathers living in a reconstituted family with own children

devote on average two hours and three quarters to care activities. Their

contribution in total care time (44%) is higher than that of traditional

fathers and men who are just stepfathers. Fathers living in traditional families

spend about two hours daily on childcare activities, while men who are just stepfathers

spend even half an hour less.

In

weekends (see Table 3), traditional fathers appear to compensate for their

lower effort during the week by nearly doubling their daily childcare time.

Fathers who live in reconstituted families with own children spend a similar

amount of childcare time (three and a half hours). The share of parental care

time taken on by fathers increases, except for fathers of reconstituted

families with stepchildren only. Reconstituted families where fathers have own

children enjoy an equal distribution of childcare time between man and woman.

These

bivariate results provide the basis for our empirical venture. They suggest

that the hypothesized relationship between family type and paternal childcare

may indeed be true. Yet, it remains to be seen whether this association hold

true when controlled for the characteristics of the fathers involved. If not, it

will prove to be nothing but spurious correlation.

4.3 An empirical assessment of the impact of

the father typology

To validate

the previous bivariate analysis we submitted the association to a multivariate test:

an OLS estimate of fathers’ primary care time controlled for explanatory

variables commonly used in time estimates (see section 2). We include fathers’ characteristics

(age, educational level, family type, time spent in the labour market, whether

self-employed or not), child characteristics (number and age) and the job type

of the mother [9]

Table 4 lists

the results for the information on care time on a typical day of the working

week (Monday till Friday). Left in the table are the estimates for the amount of

time of the father, on the right hand side we show estimates for the

proportional contribution of the father, as compared to the total effort made by

the father and mother together. [10]

For the total

amount of time a Flemish father spends on primary care in weekdays (see Table

4), the marital history of himself or his spouse does not seem to matter. Crucial

variables are the number and age of the children and the number of hours the

father puts in his job. The latter has the obvious negative sign. If the father

has a time-demanding job (more than 40 hours a week), he spends about one hour

less on his children than fathers with a standard full-time job (3.6 quarters

of an hour = 54’). Furthermore, the estimates show that fathers with more than one

child spend relatively more time on their children, but there is no strong

difference between two, three or more children. The age of the children, on the

contrary, reveals a clear distinction. The younger children are, the more time

fathers spend on their care. Interestingly, this effect also exists for school

age children. On a typical week-day, a Flemish father invests three quarters of

an hour more in primary care when his youngest child is in nursery or primary

school than when his youngest is in secondary school (aged 13 to 15). [11]

Somewhat

unexpectedly, the job time of the mother does not enter the equation. Apparently,

fathers do not compensate for the time mothers spend in the labour market, at least

not in a directly observable way. [12] At first sight, this can be interpreted as

a sign of male chauvinism, but the proportions data we will discuss below show

that the explanation is rather more complex.

Indeed,

with the equal sharing of care tasks as the primary interest of our analysis,

we cannot limit ourselves to an analysis of paternal care time only. The right

hand pane of Table 4 is at least as important. It shows what makes fathers

diverge from their average weekday contribution of 32 %. In the balance with

their partner, some of the determinants of the total amount of time continue to

bear weight. A time-demanding job reduces the proportional contribution of a

father, much as a family of two or more children increases his proportional

contribution.

Different

from our earlier analysis of the total amount of time, the type of job of the female

partner does explain much of the variance in the proportional contribution of the

father. Compared with a wife without labour market responsibilities, a partner with

a part-time job raises the father’s contribution with 12 % and a full-time job

adds 23 %.

Another difference

with the previous analysis, derives from the family type of the father. Compared

with the large majority of fathers who live with their first spouse, a father who

lives in a reconstituted family with a new spouse and his own children, caters for

a larger proportion of the primary care time (+10%). [13] Moreover, the specific

nature of the relationship with the children proves important, because fathers who

join a mother and her children from a previous relationship, do not exhibit a

rise in their care contribution and behave as ‘standard’ fathers.

The

story of week-end care is slightly different, as shown in Table 5. First, job

time is less important than during the working week, as could be expected. The

type of job of the mother is not significant, neither for the total amount of

time, nor for the proportions data. Nevertheless, a time-demanding job does

have repercussions for the father on Saturdays and Sundays too. Yet, the effect

is smaller than during the week and, moreover, has no proportions parallel,

meaning that the partner of a father with a time-demanding job does not compensate

for his reduction in care time during the weekend. The latter contrasts with

her behaviour on weekdays, when the reduction in the care time of the father is

(potentially [14]) compensated for by an increase of maternal care time (see

Table 4).

On

Saturdays and Sundays, also the number and age of the children have a different

effect. In most families, the number of children is no longer important.

Fathers spend an equal amount of time on their children irrespective of whether

they live with one, two or three children. Only the minority of fathers with

four or more children (about 6% of our sample) top the daily average with an

additional 4.6 quarters of an hour (+ 1h 8’). More important than the number of

children, however, is their age. The primary care that babies and toddlers

require, is clearly different from the time needed by youngster in secondary

school (+ 2h 15’). A similar, though smaller, difference can be observed

between the latter and children in nursery and primary school (+ 1 h 31’). As noted

in previous research, fathers tend to focus their attention, relatively

speaking, on school-age children. This is the only age group that combines an

increase in the amount with a rise in the proportion of paternal care time. This

does not necessarily mean that over the weekend mothers spend less care time

when having children in nursery and primary school, but in any case they do not

parallel the increase in care time of their partners.

Finally,

we return to the impact of the family type of the father. For our analysis of weekend

care time, the latter provide the largest part of the explained variance. [16]

As for weekdays, the family type does not alter the amount of care time of

fathers, but it does influence the proportions. A father who forms a

reconstituted family with own children caters for a considerably larger

proportion of weekend care than a ‘standard’ father (+ 14%), while the contrary

is true for a father with stepchildren only, to whom this characteristic means

an average reduction of his proportional involvement by 12%. Thus, the exact

nature of the bond between the father and the children in the household again

proves crucial to the involvement of the father.

5. Summary and discussion

With

this paper, we wanted to investigate whether a divorce or separation experience

would work as a shock to fathers as far as their contribution to parental care

time is concerned. Theoretically, several explanations could be conceived for

such a shock. First, fathers may experience a period of lone parenthood

following a separation and this experience may incite them to participate more in

parenting than before. This reasoning follows a parallel line of thinking than the

one that is developed when policy makers restrict part of parental leave to

fathers only: the mere experience will develop the taste. Yet, in Flanders most

fathers do not gain custody of their children and, hence, do not experience

anything more than shared custody. Nevertheless, even part-time lone parenthood

may work. Furthermore, divorced fathers may come to value the relationship with

their children more than they did before, because of the changes in their

family relationships. Alternatively, they may also come to recognise the importance

of an equal sharing of household responsibilities for a lastingly successful

relationship.

Our data

cannot offer conclusive evidence on whatever drives the difference in care time.

Yet, it does confirm the existence of a difference. Flemish fathers in reconstituted

families do spend more time with their children than fathers who live with

their first spouse and joint biological children. More specifically, we

observed a sizeable difference in the gender balance of primary child care time

over the weekend. With full-time work as the norm for men, the weekend is the

time of the week when fathers have most degrees of freedom regarding their time

schedule. It is exactly at these moments that fathers who live in a

reconstituted family bear 14% more of the childcare burden than ‘standard’

fathers do. However, the biological link between the father and the children he

co-resides with, proves crucial. The former result applies only to fathers who

live a mixed situation: with some children they are biologically linked to and

some they are not. If fathers are pure stepfathers, their contribution to

parental childcare goes exactly the other way round. They reduce their

contribution over the weekend.

These results

offer promising prospects for future research. We may, for example, explore the

child part of the FFCS dataset to investigate to what extent the reaction of fathers

is driven by part-time co-residence. Do they enhance their contribution on days

the children are present and reduce it on other days? Is the total care time responsive

to these variations in residence? Furthermore, we may go into the actual care

activities and detail the type of care time fathers share. Our current total

primary care concept may well conceal differences in contributions, both

regarding the type of the activity and regarding the sole or joint nature of

the activity.

In any

case, our research results suggest that the answer to the question in the title

of this paper is: yes, marital separation may bring about more equality in

parental time allocation.

Footnotes

[1] Data

from the European Community Household Panel

[2] This

is also shown by Gray (2004).

[3] This

section is largely based on research of the Centre for Population and Family

Studies (CBGS): Corijn (2005a and 2005b) and Lodewijckx (2005).

[4] This

result regards men who divorced before the age of 40.

[5] Kind

en Gezin is –among other things- responsible for the recognition,

subsidy-giving and inspection of childcare facilities.

[6]

VLAFO is responsible for the non income related aid to disabled persons (care services,

special equipment,...). For the demanders of care it organises both the intake

and the assignment of services. Furthermore it is responsible for the

recognition of care providers.

[7]

Families living in the bilingual region of Brussels are not included in the

research population.

[8]

Again, this type of families is likely to contain in part men who became

stepfathers from a previous state as bachelor, hence without a personal divorce

experience.

[9] Descriptive

information on the explanatory variables is included in the Appendix. Table A1 also

shows the reference categories for the dummy indicators.

[10] The

total effort is a crude measure summing the number of quarters of an hour of fathers

and mothers. No compensation is made for overlapping time and hence joint care

activities count for two.

[11] In Flanders

the typical age interval for secondary school children is 12 to 18 (end of compulsory

schooling), but the FFCS sample is restricted to families whose youngest child

is below 16.

[12] Previous

research shows that mothers’ time allocation tends to depend on the size of her

family.Interaction effects between the mother’s type of job and the family size

indicators might reveal an indirect effect of the type of job, but this is left

for later research.

[13] The

fact that this proportional increase coincides with a lack of change in the

amount of time spent by fathers, suggests that mothers living in reconstituted

families spend less time on primary care than mothers living with their first

spouse and children. Future research should reveal, however, whether this has

to do with the relationship between the mother and the children in the new

relationship (e.g. all children of the father) or with time these children

spend outside the household (e.g. with the ex-spouse of the father, their

natural mother).

[14]

Mathematically, it is sufficient for mothers to reduce their care time to a

lesser extent than fathers to obtain this result. Hence, a status quo of

mothers’ care effort is also perfectly feasible.

[16] Yet,

it should be noted that the multivariate regression provides weak results on this

matter, with only 5% of the total variance of the fathers’ proportion of care

time explained by the variables in the equation.

6. Appendix

7. References

- · Anxo, D., Flood, L., Kocoglu, Y., 2002, Offre de travail et répartition des activités domestiques et parentales au sein du couple: une comparaison entre la France et la Suède, Economie et Statistique, No. 352, pp. 127-150.

- · Baxter, J., 2002, Patterns of change and stability in the gender division of household labour in Australia, 1996-1997, Journal of Sociology, Vol. 38 (4), pp. 399-424.

- · Corijn, M., 2005a, Uit de echt gescheiden en dan…? De leefvorm enkele jaren na een echtscheiding in het Vlaamse Gewest, ‘Uit het onderzoek’, 13 October 2005, online on: www.cbgs.be.

- · Corijn, M., 2005b, Echtscheidingen in België: met of zonder kinderen. ‘Uit het onderzoek’, 17 October 2005, online: www.cbgs.be.

- · Craig, L., Children and the revolution. A time-diary analysis of the impact of motherhood on daily workload, Journal of Sociology, Vol. 42 (2), pp. 125-143.

- · Demo, D.H., Acock, A.C., 1993, Family diversity and the division of domestic labor: How much have things really changed?, Family Relations, Vol. 42 (3), pp. 323-331.

- · European Commission, 2005, Reconciliation of work and private life: a comparative review of thirty European countries, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Equal Opportunities, Luxemburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. online: http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/publications/2005/ke6905828_en.pdf

- · Eurostat, 2006, Crude divorce rate, online: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.

- · Deding, M. and Lausten, M., 2004, Choosing between his and her time? The market work gap and housework gap of Danish couples, 28th IARIW Conference, Cork:IARIW/CSO, 30 p.

- · Ghysels, J., 2004, Work, family and childcare: an empirical analysis of European households, Cheltenham:Edward Elgar, 287 p.

- · Ghysels, J., 2005, Holding the pencil or buying paint: parental childcare versus children’s need for extra income, the case of Belgium, Denmark and Spain, Review of Economics of the Household, vol. 3, nr. 3, pp. 269-289

- · Glorieux, I., Koelet, S., Moens, M., 2001, Een kwestie van tijd. Tijdsbesteding in Vlaanderen anno 1999, Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Sociale Zekerheid, nr. 3, pp. 533-555.

- · Gray, A., 2004, Towards a time economy of parenting, Families and Social Capital Research Group, London South Bank University.

- · Hallberg, D., Klevmarken, A., 2003, Time for children: A study of parent’s time allocation, Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 16, pp. 205-226.

- · Ishii-Kuntz, M., Coltrane, S., 1992, Remarriage, stepparenting, and household labor, Journal of Family Issues, Vol. 13 (2), pp. 215-233.

- · Kalenkoski, C.M., Ribar, D.C., Stratton, L.S., 2005, American Economic review, Vol. 95 (2), pp. 194-198.

- · Kimmel, J., Connelly, R., 2006, Is mothers’ time with their children home production or leisure?, Discussion Paper no. 2058, Bonn, Institute for the Study of Labor.

- · Lodewijckx, E., 2005, Kinderen en scheiding bij hun ouders in het Vlaamse Gewest. Een analyse op basis van de Rijksregistergegevens, CBGS-werkdocument 2005/7, online: www.cbgs.be.

- · Neuwirth, N., 2004, Parents' time, allocated for child care? An estimation system on parents' caring activities, ÖIF Papers 2004-46, Wien, Austrian Institute for Family Studies.

- · Paley, I., 2005, Right place, right time: parents' employment schedules and the allocation of time to children, ESPE 2005 Conference, Paris, ESPE/Brown University.

- · Pyke, K., Coltrane, S., 1996, Entitlement, obligation, and gratitude in family work, Journal of Family Issues, Vol. 17 (1), pp. 60-82.

- · Robinson, J.P., 2003, Changes in American parents’ use of time, University of Maryland (draft version).

- · Stancanelli, E., 2003, Do fathers care?, Paris, Observatoire Francais de Conjonctures Economiques, Sciences-Po (preliminary version).

==============================

Download a PDF version of the document:

Contact the author of the document:

* Corresponding author: Joris Ghysels

University of Antwerp

Room M-481

Sint-Jacobstraat 2

B-2000 Antwerpen

E-mail: joris.ghysels@ua.ac.be

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten